Response to Formosa Plastics’ Letter Regarding RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s Request to Rescind Parish Land Use Approval

September 15, 2020

St. James Parish Council

5800 Hwy. 44

Convent, LA 70723

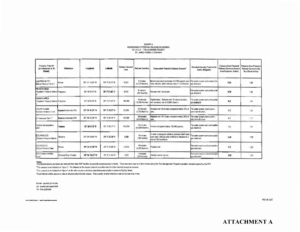

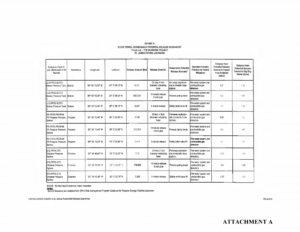

RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade submit this response to a letter sent by Formosa Plastics to the St. James Parish Council (“Formosa Plastics’ Letter”).¹ The letter discusses RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s request to the Council that it rescind its land use approval for Formosa Plastics’ planned 14-plant chemical complex. RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade called attention to Formosa Plastics’ false assertion that it had updated its site plot plan “[a]fter consultation and discussion with the Parish,” and the Council’s subsequent reliance on the plot plan showing the physical layout of the facility in relation to residential areas when making its land use decision.² Formosa Plastics’ Letter actually concedes the failing that RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade raised as the company admits that it never changed the plot plan to respond to the Council’s and the public’s concerns. The Council must rescind its land use approval made pursuant to Formosa Plastics’ apparently false pledge.

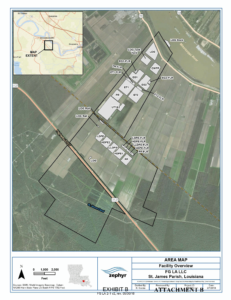

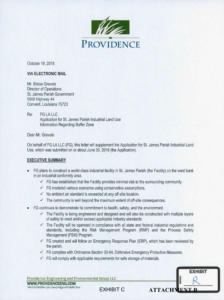

To summarize the basis of RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s request to rescind, on October 19, 2018—almost four months after Formosa Plastics submitted its initial land use application to the Parish and finalized its plot plan with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (“LDEQ”)—Formosa Plastics supplemented its land use application, stating that “after consultation and discussion with the Parish” the company “revised its plot plan” and “relocated some of its units along the western boundary, farther way from the new church and school.”³ Formosa Plastics asserted in its supplemental application that it was “listening to community concerns” and pointed to its revised plot plan and relocation of chemical manufacturing units as one of the “Steps Taken To Enhance The Health And Safety Of The Community.”⁴ Indeed, the layout of the facility is a critical issue because the Council based its decision to approve Formosa Plastics’ land use application on a Council finding that “[t]he physical and environmental impacts of the proposal are within allowable limits, and are substantially mitigated by the physical layout of the facility, and the location of the site in proximity to existing industrial uses and away from residential uses.”⁵ But, as explained below, Formosa never bothered to change the plot plan it submitted to the Council.

In December, 2019, RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade alerted the Council that there was no evidence that Formosa Plastics had revised its plot plan to move hazardous units or plants away from the church and school to satisfy the Parish’s concerns.⁶ Formosa Plastics’ Letter obfuscates the charge by pointing to an older plot plan, which predates its land use application altogether, while conceding that it never made changes to the plans it actually submitted to the Council.⁷ Specifically, Formosa Plastics said:

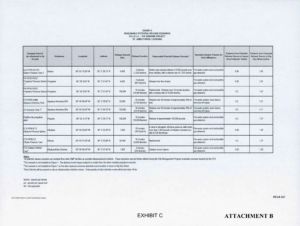

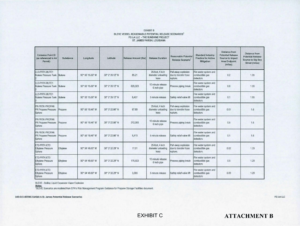

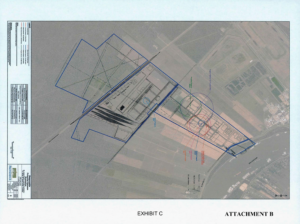

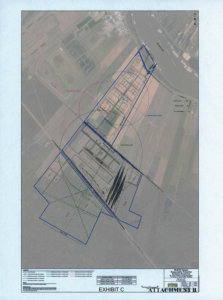

[Formosa] did move certain units or Plants closer to the western boundary. An earlier plot plan submitted to LDEQ (See Exhibit B. dated October 30. 2017) shows [Ethylene Plant 1] and certain flares along the eastern boundary. However, a later plot plan submitted to LDEQ (See Exhibit C, dated February 7, 2018) shows [Ethylene Plant 1], PR, and certain flares moved to the western boundary. It is this revision to the LDEQ plot plans which was referenced in [Formosa’s October 19, 2018 supplemental land use application] as one of several general steps FG had previously taken to enhance the health and safety of the community.⁸

This earlier plot plan submitted to LDEQ does nothing to address the issues RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade brought to the Council’s attention, and Formosa Plastics’ response creates even more questions and concerns. Following is a short timeline that illustrates the issues:

▪ Formosa Plastics submitted its initial land use application to the Parish on June 25, 2018.⁹ This 430-page application only included the final plot plan, not the older October 30, 2017 plot plan discussed in Formosa Plastics’ Letter.

▪ Formosa Plastics presented an overview of its land use application at the Parish Planning Commission July 27, 2018 meeting.¹⁰

▪ The Commission held public hearings on Formosa Plastics’ land use application on September 5, 2018 and September 19, 2018.¹¹

▪ On October 19, 2018, Formosa Plastics submitted a supplement to its land use application to the Parish, stating that “after consultation and discussion with the Parish” it “revised its plot plan” and “relocated some of its units along the western boundary, farther way from the new church and school.”¹² Despite Formosa Plastics’ claim that it had revised the plot plan, the company’s supplemental application included the same plot plan with the same site configuration and unit/plant location that it submitted with its original land use application.

This factual timeline shows that Formosa Plastics never altered the plot plan it submitted to the Parish Council. It is simply not true that Formosa Plastics made revisions to “relocate[] some of its units,”¹³ after consultation and discussion with the Parish, as it claimed.

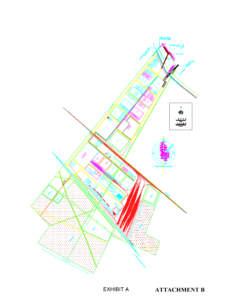

Eliding the central issue of whether it acted on its pledge to the Council, Formosa Plastics’ Letter instead highlights an alteration to the plot plan that the company apparently made months before it even submitted a land use application to the Council. But even this inapposite change does little if anything to address the hazards associated with its planned complex. Formosa Plastics contends that it had (prior to its land use application) moved one of its planned ethylene cracking plants (ET1) and certain flares from its eastern boundary to its western boundary “as one of several general steps [Formosa Plastics] had previously taken to enhance the health and safety of the community.”¹⁴ But what Formosa Plastics actually did was swap one hazardous plant for another. As illustrated in the plot plans below, while Formosa Plastics’ did move one of its planned ethylene cracking plants from the eastern side to the western side, it also moved one of its planned ethylene glycol plants (EG2) and its associated flare (EG2-FLR) from the western side to the eastern side.

October 30, 2017 Plot Plan¹⁵ February 7, 2018 Plot Plan¹⁶

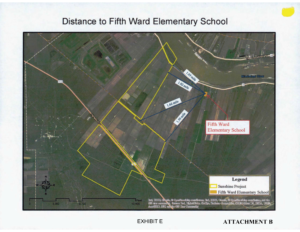

The ethylene glycol plants are the sources that would be responsible for Formosa Plastics’ ethylene oxide emissions. Ethylene oxide is a potent toxic pollutant that is linked to breast cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and lymphocytic leukemia¹⁷—and has been found by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to be far more carcinogenic than previously understood.¹⁸ Ethylene oxide is a major driver of cancer risk from industrial sources.¹⁹ Indeed, there is a national effort to reduce or eliminate ethylene oxide emissions from sources that the cancer causing chemical. One study shows that people who live within a half mile of an Illinois facility that emitted 3,058 pounds per year of ethylene oxide (a fraction of Formosa Plastics’ permitted amount of 15,400 pounds per year of ethylene oxide) had 50 percent higher ethylene oxide concentrations in their blood.²⁰ That facility is now only permitted to emit 150 pounds of ethylene oxide each year, which is about one percent of what Formosa Plastics would be allowed to emit into the air.²¹ Illinois law now prohibits the construction of new ethylene oxide sterilization facilities²² within 15 miles from a school or park in counties with populations less than or equal to 50,000.²³ In contrast, Formosa Plastics is authorized to spew enormous amounts of this potent carcinogen into the air just one mile from the St. Louis Academy, which is a predominantly Black elementary school.

Despite the risks, Formosa Plastics moved what would be one of the largest sources of ethylene oxide in the nation even closer to an elementary school. Moving a major source of ethylene oxide emissions across a 2300-acre site to the eastern side closer to the elementary school cannot, under any stretch of logic, constitute a step “to enhance the health and safety of the community” as Formosa Plastics claims.²⁴,²⁵

The Council has the power and responsibility to “protect[] and preserve the general welfare, safety, health, peace, and good order of St. James Parish,”²⁶ which includes taking action to rescind its approval of Formosa Plastics’ land use application.

Sincerely,

Corinne Van Dalen, Staff Attorney, La. Bar No. 21175

Earthjustice

900 Camp Street, Unit 303

New Orleans, LA 70130

cvandalen@earthjustice.org

On behalf of RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Citations, exhibits, and attachments below.

1 See Ltr. from Formosa Plastics’ attorney, J. King, to Formosa Plastics’ Community and Government Relations Director, J. Parks, Jan. 21, 2020 (“Formosa Plastics’ Letter”), ATTACHMENT A. RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade obtained Formosa Plastics’ Letter through a public records request for correspondence between Formosa Plastics and St. James Parish and the documents showed that Ms. Parks forwarded this letter to members of the St. James Parish Council via email.

2 See Ltr. from RISE St. James and Louisiana Bucket Brigade’s attorney, C. Van Dalen, to SJP Council, Dec. 23, 2019 (“RISE Dec. 23, 2019 Ltr.”), ATTACHMENT B (also available at https:/www.stjamesla.com/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Agenda/_01082020-223, pdf. pp. 13-40); id. at Ex. C, pdf. pp. 24-34 (Letter from Formosa Plastics’ consultant Providence to SJP Dir. of Operations, B. Gravios, Oct. 19, 2018).

3 Id. at Ex. C, p. 4, pdf. p. 27 (emphasis added).

4 Id. at Ex. C, pp. 2, 4, pdf. pp. 25, 27.

5 Id. at Ex. D (St. James Parish Council Resolution 19-07, Denying the Appeal of RISE St. James and Approving the Application of FG LA LLC under the St. James Parish Land Use Ordinance, with Conditions, Jan. 24, 2019, (“SJP Resolution 19-07”), p. 5, pdf. p. 39) (emphasis added).

6 Id. at 3, pdf. p. 15.

7 See Formosa Plastics’ Letter, p.2, ATTACHMENT A, pdf. p. 2.

8 Id.

9 See FG LA Land Use App (June 25, 2019) (on file with the St. James Parish Planning Commission as item #18-30); see also SJP Resolution 19-07, attached as Ex. D to ATTACHMENT B, pdf. p. 23.

10 SJP Resolution 19-07, attached as Ex. D to ATTACHMENT B, pdf. p. 23.

11 Id.

12 Formosa Plastics’ Supp. Land Use App., p. 4, attached as Ex. C to ATTACHMENT B, pdf. p. 15 (emphasis added).

13 Id., Ex. C. at 4, pdf. p. 27.

14 Formosa Plastics’ Letter, p. 2, ATTACHMENT A, pdf. p. 2.

15 Id., p. 2, Ex. B, pdf. p. 18.

16 Id., p. 2, Ex. C, pdf. p. 19.

17 Evaluation of the Inhalation Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide, EPA 3-66 (Dec. 2016), https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/1025tr.pdf. In addition to significant cancer risks, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (“ATSDR”) warns that acute respiratory exposure to Ethylene Oxide may cause narrowing of the bronchi and partial lung collapse. Inhalation of Ethylene Oxide can also produce central nervous system depression, and in extreme cases, respiratory distress and coma. The ATSDR also notes that children may be more vulnerable to Ethylene Oxide exposure, especially chronic exposure. Ethylene Oxide ([CH2]2O), ASTDR, https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/mmg137.pdf. EPA and the ATSDR have also warned that inhalation exposure to Ethylene Oxide can lead to spontaneous abortions. Ethylene Oxide: Hazard

18 Ethylene Oxide: History, EPA:IRIS (last updated July 28, 2018),

https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris2/chemicalLanding.cfm?substance_nmbr=1025#tab-3 (describing IRIS’s work from 2006−16 on the 2016 IRIS value for inhalation carcinogenicity); see Notice of a Public Comment Period on the Draft IRIS Carcinogenicity Assessment for Ethylene Oxide, 78 Fed. Reg. 44,117 (July 23, 2013); see Evaluation of the Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide Docket, REGULATIONS.GOV (last visited July 12, 2019) https://www.regulations.gov/docket?D=EPA-HQ-ORD-2006-0756; Evaluation of the Inhalation Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide, Executive Summary, EPA (Dec. 2016), https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/subst/1025_summary.pdf; Evaluation of the Inhalation Carcinogenicity of Ethylene Oxide, EPA (Dec. 2016),

https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/toxreviews/1025tr.pdf.

19 See S. Lerner, The Intercept, “A Tale of Two Toxic Cities: The EPA’s Bungled Response to an Air Pollution Crisis Exposes a Toxic Racial Divide” (Feb. 24, 2019),

https://theintercept.com/2019/02/24/epa-response-air-pollution-crisis-toxic-racial-divide/ (“Ninety-one percent of the risk in these communities is caused by three major pollutants: chloroprene, ethylene oxide, and formaldehyde.”)

20 See Michael Hawthorne, “Higher Levels of Cancer-causing Ethylene Oxide Found in People Living Near Medline in Waukegan, CDC Study Shows” (Dec. 11, 2019),

https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/environment/ct-medline-ethylene-oxide-blood-tests-20191211- oz4ba5eanfhxrdrjxn4ya3d4gq-story.html (“The mean concentration of ethylene oxide in their blood was about 1.5 times higher than other participants who live farther away from the company’s facility , according to Buchanan’s summary of the test results, which were analyzed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”).

21 Id.

22 The ethylene oxide-emitting facilities of concern in Illinois are sterilization facilities.

23 415 Ill. Comp. Stat. Ann. 5/9.16; see also CBS Chicago, “New Law Named After Matt Haller Puts Strict Limits On Toxic Ethylene Oxide Emissions; ‘An Everlasting Legacy’” (June 24, 20), https://lipinski.house.gov/dan-in-the-news/new-law-named-after-matt-haller-puts-strict-limits-on-toxic ethylene-oxide-emissions-an-everlasting-legacy-june-24-2019/.

24 See Formosa Plastics’ Letter, p.2, ATTACHMENT A, pdf. p. 2.

25 LDEQ has allowed Formosa Plastics to emit a staggering 15,400 pounds (or 7.7 tons) of ethylene oxide per year. See Permit No. 3142-V0, Ethylene Glycol 1 Plant, EDMS No. 11998446, https://edms.deq.louisiana.gov/app/doc/view.aspx?doc=11998446&ob=yes&child=yes; Permit No 3151- V0, Ethylene Glycol 2 Plant, EDMS No. 11998428,

https://edms.deq.louisiana.gov/app/doc/view.aspx?doc=11998428&ob=yes&child=yes. Based on the national Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), only two other sources in the U.S. reported ethylene oxide releases in 2018 that exceed the amount that LDEQ has allowed Formosa Plastics to emit. See TRI On Site and Off-Site Reported Disposed of or Other Released Top 100 Facilities for Ethylene Oxide, IASPUB.EPA.Gov. LDEQ greenlighted Formosa Plastics’ ethylene oxide sources using its outdated air quality standards and accepting the company’s claim that it can somehow burn off 99.9 percent of its ethylene oxide emissions before these carcinogenic pollutants are emitted from its stacks. The ethylene oxide emissions estimates that Formosa Plastics gave LDEQ are based on an unsupported assumption that its thermal oxidizers (or incinerators) would have a 99.9 percent combustion efficiency. See Formosa Plastics’ Ethylene Glycol 1 App, Dec. 20, 2017 (stating that “[t]he Thermal Oxidizer is expected to provide 99.9% destruction of VOC compounds,” and providing emission calculations for the thermal oxidizer showing destruction rate efficiency (DRE) at 99.9 percent), EDMS No. 10878178 at pdf. pp. 14, 98, https://edms.deq.louisiana.gov/app/doc/view.aspx?doc=10878178&ob=yes&child=yes. To put this another way, Formosa Plastics plans to route an average of 2,881.02 tons per year of ethylene oxide to each thermal oxidizer at its two ethylene glycol plants, and emit 2.88 tons per year from each thermal oxidizer after the combustion process. Id. at pdf. 97. If the combustion rate is only 99 percent efficient instead of 99.9 percent, the thermal oxidizer would emit 10 times more ethylene oxide. LDEQ has also allowed Formosa to emit ethylene oxide from flares and from fugitive (or uncontrolled) sources at its ethylene glycol plants. While the Parish has required Formosa Plastics to install monitoring along its eastern property boundary for ethylene oxide and some other toxic pollutants, but this does nothing for the people who live across the river just one half mile away. Further, there is no requirement that Formosa Plastics ever send any reports from these monitors to LDEQ, leaving open the question as to whether the Parish will have the capacity evaluate the reports for ethylene oxide emissions, which, according to the EPA “can be difficult to analyze.” See U.S. EPA, Update on EPA’s work to understand air concentrations of ethylene oxide (Nov. 6, 2019), https://www.epa.gov/hazardous-air-pollutants-ethylene-oxide/ethylene oxide-updates

26 SJP Home Rule Charter, Art. III, Sec. A, 7.b,